A-Do and Armenians in the Ottoman Province of Van on the Eve of WWI

A-Do is a leading intermediary source on the Armenian population of Van cir. 1915. This is a critical evaluation of his work Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum in 1914-1915 (Yerevan: Louys, 1917]; English translation, Van 1915: The Great Events of Vasbouragan (London: Gomidas Institute, 2017).

Gomidas Institute Studies Series

4 December 2022

A-Do (Hovhannes Ter Martirosian) and His Report on Armenians in Van, 1915

In 1917, A-Do (Hovhannes Ter Martirosian) published a report on the momentous developments that had occurred in the Ottoman province of Van at the beginning of the First World War. This report was primarily about the Ottoman entry into the war and the events that followed in the Van region. The report, entitled Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum, included a demographic profile of the Armenian population of Van province, with a listing of 450 Armenian-inhabited settlements and their (Armenian) inhabitants.1 A-Do had good credentials to prepare such a report, given his earlier publication Vani, Erzeroumi yev Bitlisi Vilayetneru (Yerevan, 1912), a book based on a study-trip that he had made to the Ottoman Empire in 1909.2 As the title implies, that study focused on the Armenian populations of the Van, Bitlis and Erzeroum provinces.3

While both works were serious accounts, Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum was written in a more popular style with very few footnotes, although it identified many of its sources in the body of its text. Such sources included the Ashkhadank newspaper of Van, individuals with whom A-Do had consulted, as well as the author’s personal observations.4

We are fortunate that A-Do also wrote a memoir, Im Hishoghoutiunneru, where he provided details of his activities during the war, including a chronological account of his movements in the Van area in June-July 1915. Again, this account includes descriptions of his various methods for collecting different information in different places.

Nevertheless, the two sets of demographic information in Vani, Erzeroumi yev Bitlisi Vilayetneru and Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum differed from each other without any comment by the author.5 A-Do clearly considered the figures in the latter publication to be of greater significance and gave them preference over those in his earlier study, although he only provided one reference regarding their provenance. He stated that the information in question, with the exception of two (unnamed) districts, was based on material from the Van Prelacy and the Aghtamar Catholicosate between 1913 and 1914. He did not provide any other details.6

Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum, 1914-15 as a Critical Source in Armenian Historiography

A number of historians have used A-Do’s population statistics in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum as a vital reference on Van in their own work. The first was Teotig, who produced Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan. He relied on A-Do’s data from Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum. Compiled in Constantinople circa 1920, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan was a complex study with significant demographic content.7 Sarkis Karayan, in his mammoth work on Ottoman Armenians, cited Teotig’s work (Koghkota) as a major source on Van, without mentioning that the data had in fact come from A-Do’s 1917 publication.8 When G. M. Patalyan prepared a demographic assessment of the Armenians of the Van region in the late Ottoman Empire, he utilised a range of major sources, including A-Do’s two aforementioned works, but he also did not discuss the provenance of the figures in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum.9 Only Raymond Kevorkian used Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum with proper citation of A-Do’s original reference relating to the Van Prelacy and Aghtamar Catholicosate, but he also included a critical addition, that A-Do had obtained these figures from the pages of Ashkhadank newspaper of Van.10

Ashkhadank and the Survey of the Province of Van, 1913

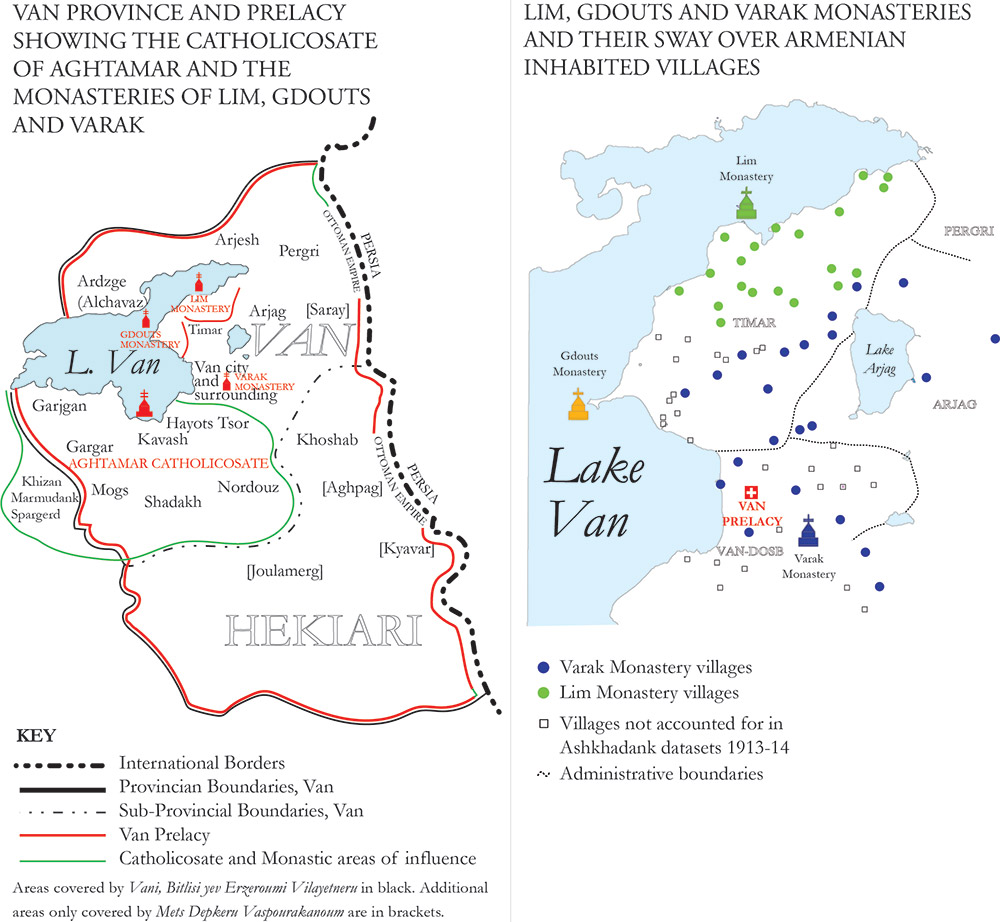

An examination of the Ashkhadank newspaper confirms that it did, indeed, publish demographic information on Armenians in Van province in 1913 and 1914. As the newspaper explained, this data was derived from the Van prelacy, the administrative centre of the Armenian Apostolic community in that province, following a population survey that had been undertaken in 1913.11 According to Ashkhadank, the survey had been requested by the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople.12 The newspaper’s description of the survey clearly suggests that it was part of the Constantinople Patriarchate’s survey across the Ottoman Empire in 1913.13 However, the survey returns that were collected at the prelacy were not forwarded to the Constantinople Patriarchate.14 Such a development likely occurred because the Van prelacy did not maintain centralised records and could not verify the data that it had received from outlying districts as required by the Patriarchate.15 This impasse, the result of poor centralised records at the Van prelacy, may have been due to peculiar local conditions in the region, such as the large number of settlements over a wide area, the additional difficulties of terrain and communication, and overlapping Armenian ecclesiastical authorities in the province, most notably Aghtamar Catholicosate’s sway over much of the Van area, but also the villages bound to Lim, Gdouts and Varak monasteries. For example, while the Van prelacy covered 450 towns and villages, the prelacies of Erzeroum, Kharpert and Bitlis, which responded to the survey, were responsible for 46, 64 and 71 settlements respectively, with no overlapping jurisdiction of other ecclesiastical authorities. Of the 450 Armenian-inhabited towns and villages in Van province, around 230 were actually under the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Aghtamar, Lim and Varak. We have no details of the villages under the jurisdiction of Gdouts Monastery. However, an earlier report, dated 13 April 1873, notes that Gdouts Monastery held sway over eight villages: Khavents, Annavank, Jrashen, Marmed, Yegmal and Amenashad, Alour, Trnashen, all of them in the Timar region.16

Moreover, although the survey in question requested information according to 21 categories, the returns that were submitted were somewhat varied in content.17 Most did not provide much of the information that had been requested. Some returns were very brief and only presented lists of Armenian inhabited settlements and the number of Armenian households, while others gave fuller returns, though none responded in full to the 1913 survey form.18

Nevertheless, the Ashkhadank newspaper saw the merit of publishing the returns that were sent to the Van prelacy as raw data. These were published in an ad hoc manner throughout 1913 and 1914. The newspaper did not provide any further correspondence that may have accompanied the returns. Although it did solicit comments from readers, no such comments were published in the newspaper. Three regions appearing in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum – Pergri, Hoshap and Saray – were not covered in the datasets published by Ashkhadank. We do not know whether these regions responded to the survey at all.

Returns Appearing in Ashkhadank and their Rendition in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum

Although the 1913 Van survey, as published by Ashkhadank, provided the substance of Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum, there were also some significant differences between them. A comparison of the two datasets, i.e., the datasets appearing in Ashkhadank and their final rendition in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum, supports the following observations.19

The information presented by Ashkhadank covered all regions of the Van province, except for Pergri, Hoshap and Saray, accounting for around 90% of Armenian inhabited towns and villages of the province. Seven of the returns in Ashkhadank are practically identical to the data in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum (the city of Van, Aghpag, Hayots Tsor, Gavash, Shadakh, Gargar and Garjgan); three returns are similar but some of the data is edited without explanation (Lim Monastery, Varak Monastery, and Ardzge [Adiljevaz]); and another seven returns are completely different, again without any comment by A-Do (i.e. Kachperouni [Arjesh], Jiulamerg, Gyavar, Mogs, Arjag, Nordouz).

The Focus of Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum

A-Do’s demographic information in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum had a narrow focus on Armenian-inhabited settlements and their Armenian populations in households and individuals. He extracted this information from the returns in Ashkhadank and entered them onto his own pre-existing list of villages from Vani, Bitlisi yev Erzeroumi Vilayetneru. This accounts for the common order of villages in both publications. By using his earlier list of villages as a guide, A-Do ensured that his final village lists in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum conformed to the administrative boundaries of the Ottoman state, as he had devised in his earlier work, and not the administrative boundaries of the Armenian church, as reflected in the actual returns sent to Van. For example, the villages of Pertag, Dzvsdan and Ardamed, which were listed in Hayots Tsor in the Ashkhadank returns, were moved into the Van-Dosp region (the central district or kaza of Van) in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum. His earlier list of villages also allowed A-Do to identify Armenian-inhabited villages that might have been missing in the 1913 returns. Such was the case for the villages of Kazogh and Dantsoud in Ardzge (Aljavaz), both of which appeared in Vani, Bitlisi yev Erzeroumi Vilayetneru but not in the 1913 figures of Ashkhadank. These villages were thus reintroduced in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum, though A-Do does not comment on how he made this arrangement.20 There were also cases where villages appeared in more than one return, such as Arjag and Mandan. These settlements can be seen in the returns of both Varak Monastery and Arjag in the Ashkhadank returns. These double entries were resolved in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum, but again, without further comment by A-Do.21

There were also certain peculiarities presented by the returns of Lim and Varak monasteries.22 While Lim only held sway over a compact group of villages in the northernmost region of Timar sub-district (nahiye), the villages under the authority of Varak were scattered over three different areas (mostly in Van-Dosp, but also Timar and Arjag), interspaced with other Armenian inhabited settlements which were not under Varak’s authority.23 25 villages in Timar and Van-Dosb were not listed under the authority of these monastic regions, and there were no separate returns from Timar and Van-Dosb accounting for these missing villages in Ashkhadank.24 These villages were included in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum.

In the cases of Aghpag, Joulamerg, Kyavar and Saray, A-Do could not make reference to Vani, Bitlisi yev Erzeroumi Vilayetneru because those regions were not covered by the earlier study. The data for Aghpag in Mets Depkeru Vasbourakanoum are almost identical to the Ashkhadank figures except for A-Do’s clerical error in reproducing some of the information, while those for Julamerg and Kyavar are modified figures, also based on Ashkhadank. There is no evidence to suggest that Ashkhadank ever printed figures for Saray, and there is no indication regarding the origin of the data for Saray in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum.

Human Errors

When working on his materials, A-Do made some minor human errors of his own. For example, in the case of Aghpag, he overlooked the village of Arag when working on his dataset in Ashkhadank and proceeded to misalign the data entries for seven villages that were listed in the same column immediately after Arag. There are also a few cases where he seems to have misread the printed figures, for example, by reading “638” as “698” for the village of Aren in Ardzge. The figures “3” and “9” look remarkably similar in the newsprint of Ashkhadank. These are minor errors that have little or no relevance to the overall figures.

In some cases, A-Do did not notice some double entries in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum, such as the village of Ermants, which appears in both the Van-Dosp and Arjag regions, and Toni, which appears in both Van-Dosp and Hayots Tsor.25 These duplications first appeared in Vani, Bitlisi yev Erzeroumi Vilayetneru and seem to have been then replicated in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum.26 Elsewhere, A-Do omitted the village of Veri Arjra (Ardzge region), which appeared in the returns of Ashkhadank, but not in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum. This omission was almost certainly made by mistake, as the list of villages in Vani, Bitlisi yev Erzeroumi Vilayetneru only had a single entry for Arjra, although the return published in Ashkhadank distinguished between “Arjra” and “Upper Arjra.”27

Regarding a pedantic but important point, A-Do also made changes to the spelling of the names of Armenian inhabited settlements. While some of these changes may have been corrections of typographical and other errors in his original sources, most were made to conform his list of villages to the phonetics and orthographic conventions of eastern Armenian. Unfortunately, these changes were not made consistently, thus adding a peculiar complexity to the information at hand. Consequently, when looking for the accurate spelling of place names (e.g for transliteration purposes), one should consult original copies of Ashkhadank or other unadulterated sources as critical references, such as Teotig’s Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutyan yev ir Hodin.

Conclusion

A-Do’s figures for the Armenian population of Van on the eve of the First World War were based on the returns of a 1913 population survey conducted by the Van Prelacy, as the results had been published in Ashkhadank in 1913-1914. A-Do drew on the information that appeared in Ashkhadank, rearranged the listing of villages to conform to Ottoman administrative regions, sought out double entries and missing settlements, and scrutinised the actual population figures before including them in his own work, Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum. Most of the datasets appearing in Ashkhadank were thus utilised without changes, though the population of many villages had minor adjustments, and in some cases, significant ones. In some areas, A-Do based his figures on entirely different sources which he did not disclose.

Any evaluation of A-Do’s final figures in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum has to take note of the author’s standing as a meticulous scholar in his own right and a keen observer who probed his subject matter and collected information when he visited Van in 1909 and 1915. Indeed, by the beginning of 1916, A-Do claimed to have amassed a “rich collection of materials” for his publication, Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum, which appeared a year later.28

However, the popular format of Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum meant that A-Do provided practically no commentary about the demographic materials he had so meticulously collected or his method of scrutinising them for his published work. The demographic information in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum was thus presented under his own authority and should be qualified as A-Do’s population figures for Van, based on the results of the Van Prelacy’s 1913 population survey, as published in the Ashkhadank newspaper in 1913-14. This qualified description is a significant clarification which reflects the provenance of Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum as a serious resource for historians working on Van in the late Ottoman Empire. While the original statistical tables collected at the Van prelacy may be lost, as well as the archival records upon which they were based, the raw datasets published in Ashkhadank remain an important intermediary source that can be consulted in conjunction with A-Do’s work today.

ENDNOTES

1. A-Do [Hovhannes Ter Martirosian], Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum 1914-15 Tvakannerin, (Yerevan: Louys, 1917). A-Do had also produced a much earlier work that could be compared, as a genre, to Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum. The earlier report was on the Armenian-Tatar clashes in Russian Transcaucasia in 1905-06. See A-Do, Hay-Tatarakan Untharoumu Govgasoum (1905-1906 tt.): Pasdakan, Vijagrakan, Teghagrakan Lousabanovtiunnyrov, (Yerevan: Ayvaziants and Nazariants, 1907).

2. A-Do, Vani, Erzeroumi yev Bitlisi Vilayetneru: Ousoumnakan Mi Ports Ayt Yergri Ashkharhagrakan, Vijakagrakan, Iravakan yev Tntesakan Droutyan (Yerevan: Koultoura), 1912.

3. A-Do also prepared a travel account of his visit to the Ottoman Empire, which was serialized in Nor Hosank in 1914. The journal stopped publishing because of the outbreak of World War One and the series was not completed. For a serous appraisal of A-Do’s 1912 publication, using contemporary sources of that period, see Robert Tatoyan, “‘Mi Kani Tver’ A-Doyi ‘Vani, Pitlisi yev Erzroumi Vilayetneru’ Ousoumnasiroutiunu (1912 t.) yev Hatykakan Hartsi Verartsartsman Zhamanagashrchanoum Arevmdahayoutyan Tvakanaki Hartsi Shourj Haykakan Mamouloum Tsavalvats Panaveju” in Tseghasbanagitakan Handes (Yerevan: Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute, 2017), No. 5(1), pp. 32-61.

4. A-Do mentions that he started writing his report, Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum, in 1916 and the work was released in January 1917. See A-Do, Im Hishoghoutyounneru, intro. By Rouben Gasapyan and Rouben Sahakyan, (Yerevan: Arm. Rep. National Academy of Sciences, 2015), p. 272. His memoir described how he had made a private visit to Van and Bitlis provinces in May-July 1915, when they were under Russian control. While there, he collected information from eyewitnesses and other details on the ground. He even became an eyewitness to much of what he described, such as the withdrawal of the Russian army from Van in August 1915 and its aftermath in the Caucasus. An examination of Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum shows that A-Do made extensive use of the Ashkhadank newspaper, especially when describing the Armenian defence at Van in April-May 1915. Much of A-Do’s analysis of events can be independently corroborated alongside information collected from Armenian refugees who managed to flee to the Caucasus in 1915. See Amatouni Virabyan (ed.), Hayots Tseghaspanoutiounu Osmanyan Tourkiayoum: Verapradznyeri Vkayovtiunner Pastatghteri Zhoghovadzou, Hador 1, Van Nahang, (Yerevan: Hayastani Azgayin Arkhiv, 2012). The first volume of this three-volume set is devoted to the province of Van.

5. The reference here is to the common denominator to the two works, the Armenian population of the Van province.

6. A-Do, Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum, p. 11. A-Do states that only two regions were not based on sources from the Van Prelacy and Aghtamar Catholicosate. Presumably these were regions that were not covered by Ashkhadank between 1913 and 1914. According to our own examination of the Ashkhadank newspaper and A-Do’s work of 1917, there were three such areas, not two. They were Pergri (734 households), Hoshap (252 households) and Saray (118 households).

7. See Teotig, Koghkota Hay Hokevoraganoutuan yev ir Hodin Aghedali 1915 Dariin, ed. Ara Kalayjian (New York: St. Vartan Press, 1985). Teotig mentions A-Do as his source without mentioning any other details. See ibid., pp. 35-37.

8. Sarkis Y. Karayan, Armenians in Ottoman Turkey, 1914: A Geographic and Demographic Gazetteer, (London: Gomidas Inastitute), 2018, pp. 482-526. Alongside Teotig’s work, Koghkota, Karayan also uses A-Do’s earlier work, Vani, Bitlisi yev Erzeroumi Vilayetneru. Karayan does not cite A-Do’s Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum in his bibliography and was probably unaware of its existence.

9. G. M. Patalyan, “Vani Nahangi Hayabnak Bnakavayreri Tsoutsagnern Usd Arantsin Gavarakneri yev Kyovghakhberi” in Banber Yerevani Hamalsarani, Yerevan, 1987 (2), pp. 83-110. Patalyan assumes that A-Do had seen no-longer-extant church records in Van as the basis of the figures in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum. He does not trace their provenance to the Ashkhadank newspaper as a critical intermediary source.

10. Raymond Kevorkian and Paul Paboudjian, Les Armeniens dans l’Empire ottoman à la veille du genocide, (Paris: Arhis. 1992), p. 511. However, Kevorkian did not specify which issues of Ashkhadank A-Do had used when making his observation.

11. Ashkhadank, 22 June 1913.

12. For more information about the Constantinople Patriarchate’s 1913 population survey, see Raymond Kevorkian and Paul Paboudjian, Les Armeniens dans l’Empire ottoman à la veille du genocide, (Paris: Arhis. 1992).

13. The survey requested detailed, tabular reports, according to a common questionnaire, accounting for the number of Armenians, Turks, Kurds, and other ethnic and religious groups in each town and village, as well as the value of Armenian national properties, bantoukhd workers away from the village, schools “and other details.” Ashkhadank, 22 June, 1913.

14. The correspondence records of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople regarding the 1913 survey include a note from Van stating that the prelacy did not keep centralised records [and did not have the information that had been requested]. See AGBU Nubar Archives, Paris, DOR 3/4. However, Lim Monastery (in the Van province) sent a separate response to this survey directly to Constantinople (dated 23 October 1913), as well as a return to the Van prelacy, published in the Ashkhadank newspaper on 29 June 1913. The two sets of figures from Lim are practically identical with only some minor differences concerning the number of bantoukhds. The return to the Patriarchate provided all of the information that was requested, including the number of churches, clergymen, Islamized Armenians and the destination of bantoukhds, as well as the Kurdish population of villages in terms of individuals. See AGBU Nubar Archives, Paris, DOR 3/1.

15. The survey forms required the returns to be endorsed by the central administrative and religious councils, as well as the local prelate. We can presume that the Van prelacy did not have the requisite centralised records to validate the information that it had collected from outlying areas prior to forwarding such materials to Constantinople. However, Teotig presents us with two informal sets of summary figures in the correspondence of the Armenian Prelate of Van, Bishop Hovsep Sarajian, dated 17 July 1913, and the Catholicosate of Aghtamar, in 1914, both comparable to A-Do’s datasets in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum. These two references validate the significance of the data gathered in Van, even if the datasets upon which they were based were not forwarded to the Constantinople Patriarchate. See Teotig, Koghkota, p. 33-34, 37-8. The original documents concerning these two references have not been located to date. They may be among the papers of the Constantinople Patriarchate now kept at the AGBU Nubar Library in Paris.

16. See Yeremia Devgants, Janabahortoutiun Partsr Hayk yev Vasbouragan (1872-1873 tt.), ed. and intro. by H. M. Poghoryan (Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences), p. 247.

17. The full list of categories were: 1. Name of village; 2. Armenian (Apostolic); 3. Armenian (Catholic); 4. Armenian (Protestant); 5. Total Armenian; 6. Armenian households (total); 7. Turks; 8. Circassian; 9. Kurdish; 10. Nomads; 11. Others; 12. Bantoukhts; 13. Community Properties (value); 14. Churches; 15. Monasteries; 16. Boys’ Schools; 17. Girls’ School; 18. Students (total); 19. Clergymen; 20. Islamised Armenians; 21. Other [destination of bantoukhts].

18. The 1913 survey included 22 categories of information. The most detailed results generated in the province were from the city of Van, and the monasteries of Lim and Varak.

19. Our study is based on the following returns to the 1913 survey of the Van province: Van city, Ardzge (Adljavaz), Kachperouni (Arjesh), Arjag, the parishes of Timar and Varak monasteries (covering villages mostly in Timar but also Van-Dosp and Arjag), Hayots Tsor, Gavash, Shadakh, Gargar, Garjgan, Mogs, Nordouz and Aghpag. These returns accounted for well over 90% of Armenians in the Van province.

20. We can confirm that these villages did not appear in either Adiljevaz or the neighbouring Kachperouni (Arjesh) region. We can also state that Kazokh and Dantsoud were listed as Armenian inhabited villages in Adiljevaz in V. T. Mayevski, Voyenno-Statisticheskoe Opisaniye Vanskavo i Bitliskavo Vilayetov, (Tbilisi: General Military Staff of the Caucasus Region, 1904), p. 28.

21. Arjag and Mandan were included in the returns of both Varak Monastery and Arjag diocese. A-Do chose the data from the latter list over the former one. See Ashkhadank 29 June 1913 (Lim Monastery) and 3 August 1913 (Arjag diocese).

22. We did not find any returns from Gdouts monastery in Ashkhadank. However, according to correspondence from the prelate of Van, Bishop Hovsep Sarajian, dated Van, 17 July 1913, Gdouts was a separate monastic region with authority over a number of villages. According to this note, the monastery counted approximately 6,000 Armenian inhabitants, 14 churches and 3 monasteries under its authority. See Teotig, Koghkota, p. 34. The monastic villages of Gdouts could account for the unaccounted villages in Timar region, after the monastic villages of Lim and Varak are taken away.

23. There is no data provided by Ashkhadank covering the residual villages in Timar, i.e., villages not covered by the returns of Lim and Varak monasteries. One could also add the monastic villages belonging to Lim Monastery.

24. The missing villages were Timar (13 villages): Drlashen, Amenashad, Annavank, Marmed, Keoprikeoy, Khavents, Aliur, Yegmal, Jirashen, Pert/Nor Kiugh, Shvakar, Tashoghli; Van Dosp (12 villages): Tsorovants, Goghbants, Kouroubash, Pertag, Dzvsdan, Ardamed, Lamzgerd, Tarman, Farough, Vosgepag, Ermants, Sevakrag.

25. The village of Ermants in Ashkhadank is recorded as a mixed Assyrian and Kurdish village in the Arjag region. However, A-Do does not use the Ashkhadank figures for Arjag in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum, but he also does not indicate his alternative reference. A separate, slightly earlier source also locates the villages of Ermants in Arjag and Toni in Hayots Tsor (and neither one in Van-Dosp). According to this source, Ermants had a mixed Armenian, Kurdish and Assyrian population (with 20, 18 and 15 households respectively). See Vladimir Mayevski, Voenno-Statisticheskoe Opisanie Vanskago i Bitlisskago Vilayetov, Tiflis: Russian General Staff, 1904, p. 11 and 13.

26. Unfortunately, there were no returns for Van-Dosp in Ashkhadank, but in all likelihood, these duplications started with Vani Bitlisi yev Erzeroumi Vilayetneru and were then included in A-Do’s later work.

27. A-Do, Vani, Bitlisi yev Erzeroumi Vilayetneru, p. 43. A-Do has taken the figure for Verin [Upper] Arjra and omitted the figure for Arjra in Ashkhadank when compiling his figures for this region in Mets Depkeru Vaspourakanoum.

28. Im Hishoghoutiunneru, p. 225 and 272.

Gomidas Institute,

42 Blythe Rd., London N3 1PR.

Email: info@gomidas.org