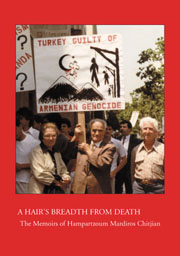

A Hair’s Breadth from Death

London : Gomidas Institute, 2021 (2nd ed.)

xx + 434 pp., maps, photos., illust., gloss.,ISBN 978-1-909382-62-6, paperback,

UK£35.00 / US$45.00

To order please contact books@gomidas.org

A Hair’s Breadth from Death represents one of the key memoirs of the Armenian Genocide to date. Written as an autobiography, Hampartzoum Chitjian (1901-2003) fleshes out, in great detail, the fate of Armenian women and children who were not "deported” in 1915, but separated from their parents for assimilation into Turkish and Kurdish households. According to some estimates, close to 200,000 Armenians were targeted for such assimilation during the genocidal process, and only a fraction of them managed to revert back to their Armenian identity after the defeat of Ottoman Turkey in 1918. Chitjian survived the Genocide in the Kharpert plain, until 1921, when he escaped to Mexico, and later moved to Los Angeles in the United States.

On the eve of the 1915 Armenian deportations, Chitjian’s father took his four sons to a Turkish orphanage in Perri, with the hope that they would somehow survive. The remaining Armenian population of Perri was soon deported and killed. Those fateful days became a turning point in Chitjian’s life, as the world he knew collapsed around him, and he embarked on an Odyssey of survival—picking up the pieces of his lost world wherever possible. The bulk of his memoirs are a detailed, blow-by-blow account of his survival in Turkish and Kurdish families, and his escape to the new world. During this period he found surviving relatives, got married, set up his own family, and become a contributing member of Armenian communities in Mexico City and Los Angeles.

Yet the Armenian Genocide remained an ever-present element in his life, as he observed new generations of Armenians who were denied knowledge of their roots, their ancestral homeland (their yergeer), and who assimilated as a matter of course. His experience of the Genocide never ended; it just entered new phases over the decades, until his own death in 2003. Perhaps it is for this reason that, like many other survivors of the Genocide, he felt compelled to write down his thoughts and memories as a debt to his family, the people of Perri, and the quest for justice he felt compelled to champion.

His memoirs are accordingly written in a passionate, forthright, and unabashed style. With his unconventional style, use of vernacular Armenian, Turkish and Kurdish terms, Chitjian expresses his fury as a survivor of the Armenian Genocide in the modern world. How could the world forget the crime that was committed against the Armenian people? How can Turkish governments today continue to deny the genocide of Armenians? And how can Armenian community leaders and political parties fail to unite against this injustice.

Chitjian’s work makes compelling reading, and can often be extremely disturbing. It is over 400 pages long and includes over 150 maps, diagrams and photographs, as well as a glossary of terms. It is a true landmark of a primary account of the Armenian Genocide.

On the eve of the 1915 Armenian deportations, Chitjian’s father took his four sons to a Turkish orphanage in Perri, with the hope that they would somehow survive. The remaining Armenian population of Perri was soon deported and killed. Those fateful days became a turning point in Chitjian’s life, as the world he knew collapsed around him, and he embarked on an Odyssey of survival—picking up the pieces of his lost world wherever possible. The bulk of his memoirs are a detailed, blow-by-blow account of his survival in Turkish and Kurdish families, and his escape to the new world. During this period he found surviving relatives, got married, set up his own family, and become a contributing member of Armenian communities in Mexico City and Los Angeles.

Yet the Armenian Genocide remained an ever-present element in his life, as he observed new generations of Armenians who were denied knowledge of their roots, their ancestral homeland (their yergeer), and who assimilated as a matter of course. His experience of the Genocide never ended; it just entered new phases over the decades, until his own death in 2003. Perhaps it is for this reason that, like many other survivors of the Genocide, he felt compelled to write down his thoughts and memories as a debt to his family, the people of Perri, and the quest for justice he felt compelled to champion.

His memoirs are accordingly written in a passionate, forthright, and unabashed style. With his unconventional style, use of vernacular Armenian, Turkish and Kurdish terms, Chitjian expresses his fury as a survivor of the Armenian Genocide in the modern world. How could the world forget the crime that was committed against the Armenian people? How can Turkish governments today continue to deny the genocide of Armenians? And how can Armenian community leaders and political parties fail to unite against this injustice.

Chitjian’s work makes compelling reading, and can often be extremely disturbing. It is over 400 pages long and includes over 150 maps, diagrams and photographs, as well as a glossary of terms. It is a true landmark of a primary account of the Armenian Genocide.